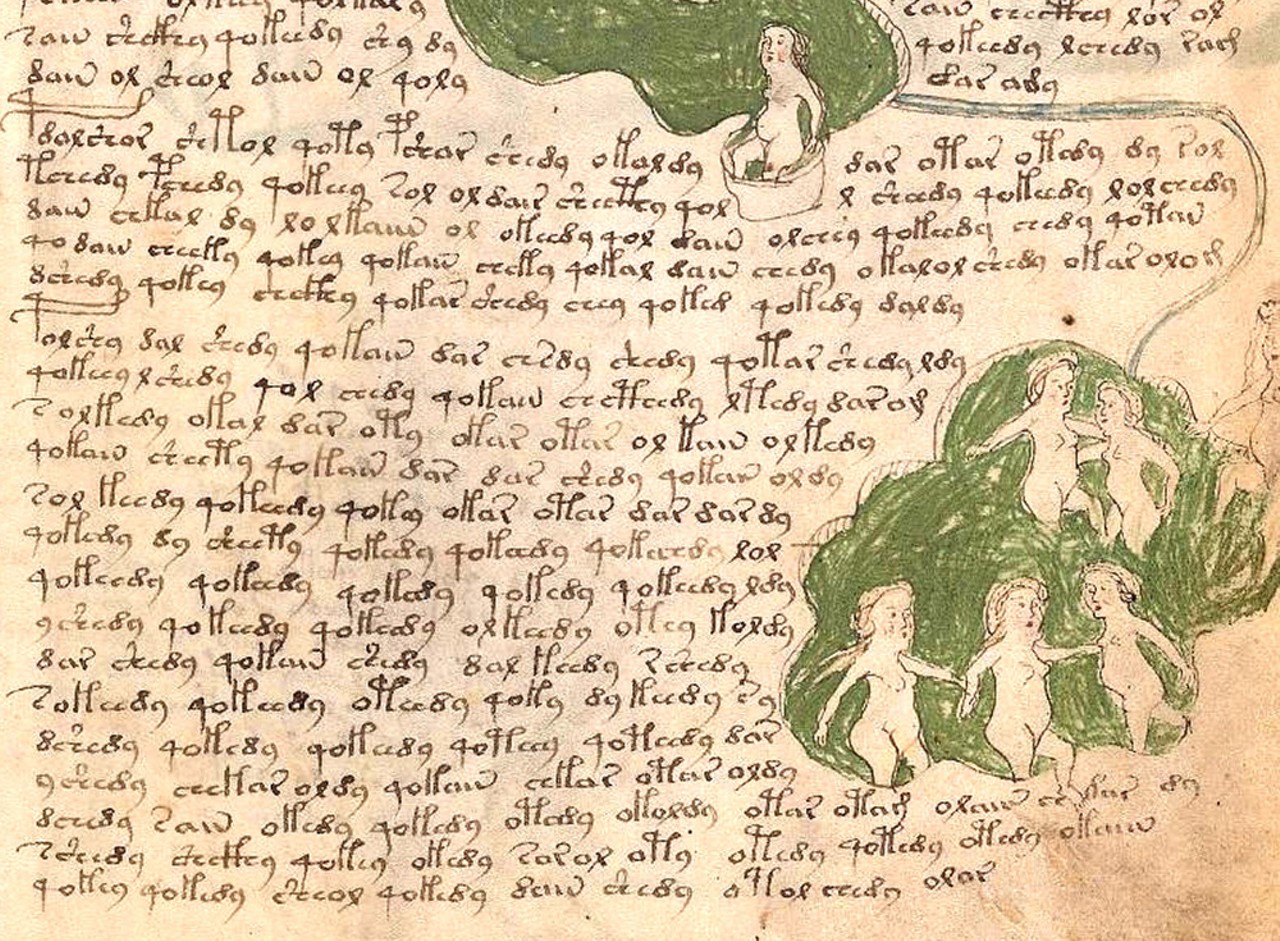

The gifted William Friedman – chief cryptoanalyst in the US Army’s Signal Intelligence Service – spent 30 years trying to crack the secrets, without success.Īt the heart of this wordy whodunnit was a Polish-Lithuanian book dealer with revolutionary tendencies and famous friends: a man called Wilfrid Voynich. To say that he led a colourful life is something of an understatement. Born in what is now Lithuania in 1865, he got himself arrested for his socialist activities and imprisoned in Siberia, only to escape and make his way to London. There, he established a second-hand book shop that was patronised by the man who would become Sydney Reilly, ‘Ace of Spies’.īut it was in a Jesuit seminary outside Rome in 1912 – during a book-buying expedition – that Voynich apparently discovered the manuscript to which he would give his name. Unusual things found in medieval manuscriptsĪppended to the manuscript, and no doubt firing Voynich’s imagination further still, was a letter that appeared to shed some light on the document’s history.Voynich, it appears, instantly realised that he had chanced upon something very special. The correspondence, written in 1665 by imperial physician Johannes Marcus Marci, claimed that the manuscript had once belonged to the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who reigned from 1576 to 1612. " Decoding Anagrammed Texts Written in an Unknown Language and Script" appeared in Volume 4 of the Transactions of the Association of Computational Linguistics.Its next owner was apparently a Prague-based alchemist called Georg Baresch who, Marci tells us, “devoted unflagging toil” to the quest of deciphering the text and “relinquished hope only with his life”.

Kondrak and Hauer are part of the University of Alberta's Department of Computing Science, with an international reputation for excellence in artificial intelligence research. Not only do we want to talk to computers in our language because it's easier and more convenient but also there is a lot of information that exists in the form of written word. "Natural language processing helps computers make sense of human language. There are so many ambiguous meanings that we don't even realize," said Kondrak. "We use human language to communicate with other humans, but computers don't understand this language, because it's designed for people. He said he is looking forward to applying the algorithms he and Hauer developed to other ancient scripts.Īn avid language aficionado, Kondrak is renowned for his work with natural language processing, a subset of artificial intelligence defined as helping computers understand human language.

Decoded voynich manuscript full#

Without historians of ancient Hebrew, Kondrak explained that the full meaning of the Voynich manuscript will remain a mystery. It's a kind of strange sentence to start a manuscript but it definitely makes sense." "It came up with a sentence that is grammatical, and you can interpret it," said Kondrak, "she made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people. "It turned out that over 80 percent of the words were in a Hebrew dictionary, but we didn't know if they made sense together," said Kondrak.Īfter unsuccessfully seeking Hebrew scholars to validate their findings, the scientists turned to Google Translate. Assuming that, they tried to come up with an algorithm to decipher that type of scrambled text.

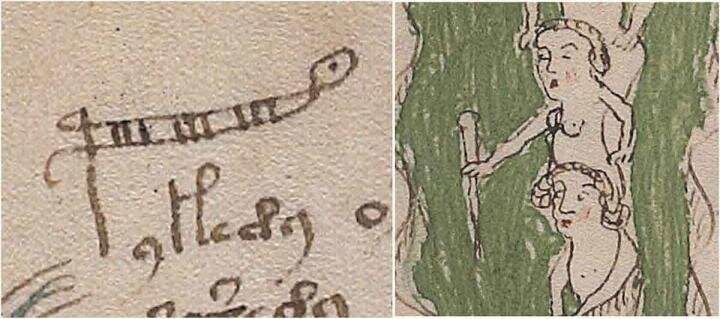

Kondrak and Hauer hypothesized the manuscript was created using alphagrams, defining one phrase with another, exemplary of the ambiguities in human language. "And just saying 'this is Hebrew' is the first step. After running their algorithms, it turned out that the most likely language was Hebrew. The scientists initially hypothesized that the Voynich manuscript was written in Arabic. Kondrak and Hauer used samples of 400 different languages from the "Universal Declaration of Human Rights" to systematically identify the language. Their first step was to address the language of origin, which is exquisitely enciphered on hundreds of delicate vellum pages with accompanying illustrations. Kondrak and his graduate student Bradley Hauer set out to use computers for decoding the ambiguities in human language using the Voynich manuscript as a case study. This ancient mystery made its way to the artificial intelligence community, where computing science professor Greg Kondrak was keen to lend his expertise in natural language processing to the search. The mysterious text in the 15th century Voynich manuscript has plagued historians and cryptographers since its discovery in the 19th century. Computing scientists at the University of Alberta are using artificial intelligence to decipher ancient manuscripts.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)